We’ve just returned from the most amazing talk given by Dr Ian McLeod of the Western Australian (WA) Maritime Museum who gave the 2015 Stanhope Oration as part of CONASTA 2015 in Perth, WA. It was entitled, The application of chemistry to conserve our shared heritage. Amongst a host of other fascinating topics, Dr McLeod spoke of his work in the preservation of WA indigenous rock art and in particular on his work on the depictions of the Wandjina in the Kimberley region of far North WA. Here’s Julie Wungundin talking about the Wandjina.

This grabbed my attention because I read The Biggest Estate on Earth, by Professor Bill Gammage last year (and here he is talking about it) and I developed an obsession with finding out more about the scientific knowledge of Australia’s first peoples. I figured there was no way you could survive (actually, not just survive, but thrive) on one the harshest continents on Earth without having a complex understanding of the ecology, meteorology, plant and animal biology (and their fire responses) and geology. That set me on a personal mission to finding out more about what they knew and understood. And this brings me to Dr McLeod’s talk.

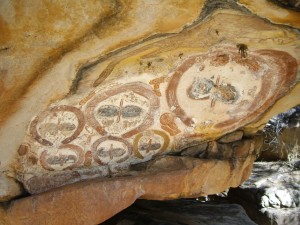

Dr McLeod told us the story of travelling out to study the Wandjina in what to me, sounded like the season in the build up to the Wet: 40 degrees Celcius in the shade and around 90-95% humidity. Absolutely stifling, or so I’ve been told. The white pigment you see in this rock art is called huntite, Mg3Ca(CO3)4, and it has the peculiar property of swelling as the humidity rises thanks to the carbonate. Due to the traditional practice of retouching the rock art, this layer of huntite is sometimes 40 layers thick. You’ll see why I think this is important later.

Source: By Whinging Pom from Everywhere, Australia (Wandjina Rock Art) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

The First Peoples of the Kimberley tell how the Wandjina, if pleased, would bring the rains, that is the annual Wet. If displeased, they would bring floods, cyclones and lightning. Now think back to the property of huntite expanding with the rise in humidity. They would have watched the Wandjina ‘grow’ building up to the Wet and then ‘shrink’ during the Dry. The rock and the Wandjina would have been alive directly communicating with them as the annual cycle of growing and shrinking occurred over the year as the seasons passed from Wet to Dry and back to Wet again.

This is the hypothesis I’d like to propose and something I’d like to explore further. Were the First Peoples watching the Wandjina to make predictions about future rain events? Is there a correlation between the length of the build up to the Wet (and therefore the humidity) and the amount of ‘growth’ of the Wandjina? Did they then use this knowledge to inform them of potential severe rain events and whether to move to safer areas? Did they use this knowledge to fire the land knowing the rains would arrive in a day or two to take advantage of the newly laid ash layer?

Without a background in pre-1788 Australian history or Australian indigenous cultures I have no idea, but it’s definitely something I’d like to explore further in the future. I think we have a long way to go in gaining a true understanding and appreciation of the complex knowledge systems Australia’s First Peoples have built up in their 50,000 year occupation of Australia and I’d like to play a small part in that in bringing that to the public consciousness.

Oh, and happy NAIDOC Week everyone.